|

Part 3 - Stroke Order and Radicals Part 4 - Yoda Speak and Good News Bad News Learning to See Chinese

Characters Part 2 If you somehow managed to stumble onto this page without reading my Introduction to Reading Chinese Characters, please go back and read it first. I'm making a serious attempt to keep this discussion progressive, and things I say next are going to assume you know things I've already said. In other words, this is not one of those programmed learning books where you can just dip in anywhere and expect to know what's going on. I said we would talk about a few things later. Since this is later, here we go. You might wonder how

people who can't tell from their written words how things should be

pronounced, even roughly, go about telling each other

how to pronounce anything without face to face contact. You

might also wonder how they can look up a word in a dictionary,

or input a word into a computer. The answer is that the

Chinese have a second writing system called

Pīnyīn is the officially recognized standard system for representing Chinese characters using the Roman alphabet and it virtually duplicates the "sinogram" or Chinese character system. I'm not going to say too much more about pīnyīn. There have been attempts to "Romanize" the Chinese language ever since Marco Polo stumbled into China, and quite a number of systems were established just to add to the confusion, which is why when I was a child Beijing was called Peking. If you are interested in this subject, there's lots of information on the Internet. For starters, I'd recommend clicking on this link to History and Prospect of Chinese Romanization by Bemjamin AO Firsst Byte U.S.A. bao@fbyte.com or just plugging something appropriate like "history of pinyin" into Google and going from there. All I want to do is talk about how pīnyīn works. It is possible to look up a word in a Chinese dictionary without using pīnyīn, by using a "radical index" that is organized by stroke number and page references. You do remember radicals? If not, go back and re-read the introduction. Most modern dictionaries use a system that combines stroke order with pīnyīn, and lists words in alphabetic order according to their pīnyīn transcription, so that they have at least some of the advantages of alphabetic listings. To look up a character in a Chinese dictionary, you first pick the most promising radical and find it in a list that is organized by the number of strokes. As you can see from the page above, this gives you a reference to another page which lists all the characters that are formed in combination with that radical, and there you will find the actual character you are looking for, someplace down the list, along with another page reference number.

Turning to this second page reference number you can find the

character, a pīnyīn transcription of the character so you know

how it is pronounced, and a definition. The dictionary

will then go on to list other words that are formed in combination

with that character, but it won't bother to tell you the

pīnyīn for these additional characters. To figure that out you

have to go back to the radical index and look them up.

Hey, just for fun let's walk through the process of looking up

a word. We'll cheat this time. We'll look up a word we

already know, so we actually could simply look it up

alphabetically by its pīnyīn name. But just to demonstrate how

simple this is, we'll look it up as if we'd never seen it

before. So here goes. Let's pretend we just "met a tiger

in the path" when we stumbled on to this unknown character: To start with, we

pick the first radical we come to, and that is

One last thing I should mention. Not all dictionaries use the same system for radical indexing, so check and make sure you like the system in use before you spring for a dictionary. The only slight break this all gives you is that the characters are organized according to their pīnyīn alphabet order, so if you hear a word you have a small chance of finding its character by going to the pīnyīn. I say a small chance because the word qi, to take just one example, can be created with 177 different characters and takes up twelve pages in the Chinese side of my Chinese-English dictionary. If I were trying to look it up, there's a good chance that I didn't hear it right and should be looking for chi, which can have 124 characters and is spread over another 6 pages. Speaking of qi reminds

me of one of my favourite Chinese words. One of the meaning of

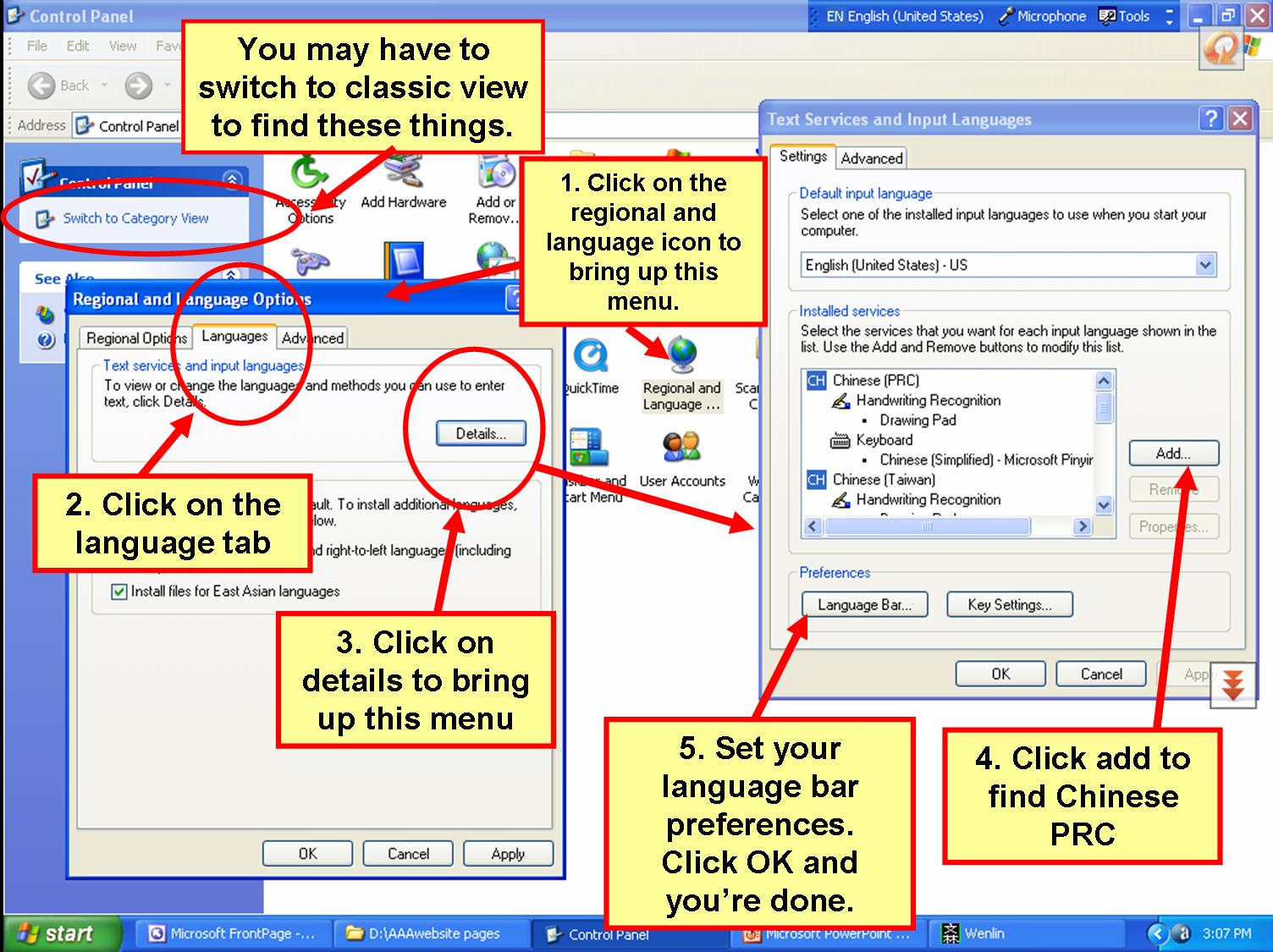

It's also possible to enter Chinese characters into a computer using a system that converts the QWERTY keyboard into character strokes, if you have the appropriate software. I'm told this system is actually much faster than using pinyin, but it is unforgiving when it comes to stroke order and difficult to learn. Most Chinese people input Chinese characters for their cell phone text messages using pinyin.

Again, Dikk Kelly has done a great job of showing how to do this on your computer. So if you have any trouble with what I have written above, just click here to see his demonstration. Pīnyīn uses a few letters in places that seem strange to us foreigners. For example, the letter x begins many words. It is pronounced more or less like an sh, but with the tongue at the front of the mouth and a more sibilant quality. I find it difficult to hear the difference between xiao and shao, but there must be one because my Chinese teachers keep correcting my pronunciation and they aren't happy until I have my lips pulled back in a rictus sardonicus grin and my tongue tight to my front teeth. Another letter that confuses me is the letter q, which begins many words and seems to be pronounced exactly like a ch. Except it isn't. But it only seems to change with the vowel that follows it, not on its own. And then there's zh, which is pronounced like a j as in "job" but with the tongue pulled as far back into the mouth as you can get it without hurting yourself. Again, I have a hard time hearing the difference this makes but others tell me it's very important. And finally we come to the most famous characteristic of the Chinese language, the tones. There are five of them, if you count the fifth tone, which is no tone at all. They are represented on pinyin words by 1. a flat line, 2. a rising line, 3. a falling and rising line, 4. a falling line, and 5. no line.

Because I'm mostly interested in talking about Chinese characters, I'm not going to go too far into pronunciation. Suffice it to say that the first tone, the flat tone, is high pitched and even and sounds a bit like singing the word on a slightly higher note. The second tone is one I find really easy, because it is the same tone we use when we turn a word from a statement into a question, or express skepticism. It actually turns many Chinese words into words of two syllables. (Try saying "yeah" like you want the speaker to continue talking or clarify something, and there's a good chance you'll be using the second tone.) The third tone starts high and falls, then gets back up again. It also tends to lengthen the words, often quite elaborately. (Try saying "yeah" again, but this time very slowly and thoughtfully, like you think that answer might be correct but you're not sure. You are probably approximating the third tone.) The fourth tone makes a word really short and abrupt, like you are spitting it out or trying to get it over with. You can't exaggerate this too much for a Chinese speaker, and it is the reason why so much Chinese conversation sounds angry. Tones are a lot less troublesome than you might think. They make a very clear and distinct difference to the sound of a word, so once you learn how to pronounce them they don't cause too much of a problem. Unfortunately, we foreigners simply tend to forget to use them, so our speech sounds very flat to the Chinese. Are tones important? Well, yes. Consider these three words:

All have the same pronunciation but different tones. The first means dog food. The second means dog house. The third means dog poop. So you might say the tones are fairly important in some situations. The tones are only shown with the pinyin pronunciation guide, not with the Chinese characters. Sometimes, if the computer or typewriter being used doesn't put these marks over letters easily, they are indicated as numbers following the pinyin. So ma3 is the same thing as mǎ, only a lot harder to interpret because you have to remember which tone is given which number.

On at least one occasion I've used the

tones as another method for remembering the meaning of a word.

For example,

Notice the yue4

radical at the bottom of this character. Like I said, it's one of

the most common elements in Chinese writing. Ruth, who is

concentrating on food words and reading labels as an aid to

shoppers, tells me that huá

is also the word

as in

By now you might be noticing the Chinese penchant for homonyms - words that sound the same but have different meanings. huā not only means "flower" but also forms the first part of "peanut", huā shēng jiàng. The rest of "peanut" is shēng, meaning "give birth" so "peanut" is "flower born". I suppose this isn't so surprising, given that "peanut" in English literally means "pea (as in like the vegetable) nut". English is just as bad as Chinese, if not worse. We're just used to it, and we don't even notice the duplications in our own language. Each Chinese character is only one syllable. This came as a revelation to me and I hope it surprises you, because otherwise you know far too much about Chinese to be reading this. And each Chinese character has a meaning all on its own, which should be no surprise at all. What probably will surprise you is that the "words" in Chinese very often are more than one character long, and the characters get used over and over in an infinite number of combinations. So when somebody tells you that you only need to recognize 2,000 characters to read the entire works of Chairman Mao, this is true. But it's also a deception. We have many occasions where we can recognize every single character in a sign or notice, and still not have a clue what it all means. Take the character

lao, as an example. Lao with shi

Lǎo with

different shi

Lǎo with

yet another shi

Lǎo with hu Lǎo with

jia ("home")

Lǎo with dà

Lǎo with

ren

Lǎo with bǎn

Lǎo with

tai tai

Lǎo with

shu

Here's one of my favourites:

Lǎo with po

Lǎo xiang

Lǎo yī

bèi

Lǎo ya

And these are just some of the words

with lǎo in the beginning. It also

forms words by taking a place in the middle, such as in

ān lǎo yuàn

or bǎi lǎo

huì And just to wind this all up,

here is a great one: chī jiǎo

zi lǎo hu, literally "eat dime tiger", which is a "slot machine" (a dime in Chinese is a jiǎo = 1/10th of a yuan.) And so it goes for hundreds of "words" formed by combining lǎo with something else, to get a completely altered and in many cases bizarre and idiomatic meaning. So if you think that learning a couple of thousand characters will let you read a newspaper, I'm sorry to disappoint you but think again. You actually need to learn the language as well. To make things just a bit more difficult, as if that were a good idea, the Chinese writing makes no attempt to group characters that form words together, so you have no way to know that lǎo actually goes with shu and means "mouse", instead of going with something else and meaning "old", or that huā actually goes with shēng to mean "peanut" and not with something else to mean "flower". It's a bit like what would hap pen if Eng lish words were writ ten as sep ar ate syl lab les, ex cept in this case each and ev er y sil lab ble has a mean ing of its own to add to the con fus ion. And this is definitely enough for now. Please let me know if you have any comments or criticism, and particularly let me know if you enjoy reading this. I get my energy from encouragement. david@themaninchina.com For my Chinese students, and others who can actually read Chinese characters, if you found anything you consider a mistake, or anything that needs to be discussed, please also send me an email. david@themaninchina.com Thanks for reading. Return to Seeing Chinese Characters Part 1 Mosey Along Now to Seeing Chinese Characters Part 3 The Man in China archive index

*I have several reference books from which I have learned the little I know about reading Chinese characters. Anytime I am quoting one of them directly, I'll try to give credit where credit is due. The one I use most often is actually software installed on this computer. It's amazing, and allows me to have instant translations of English into Chinese with both the character and the pinyin pronunciation guide. In addition I can use it to look up characters I don't know by searching the radicals , find combinations of characters that form words (listed by most common), and get historical information about character origins and evolution. It's fabulous software folks, and if you can find it someplace it's worth whatever you pay for it. Wenlin Software for

Learning Chinese version 3.0 Copyright [c] 1997 - 2002 the Wenlin

Institute In addition I have a stack of books for learning Chinese: The one that I get much of my background information from is "A Key to Chinese Speech and Writing" by Joël Ballassen (University of Paris 7) with the Collaboration of Zhang Pengpeng (Beijing Language and Culture University) and Christian Artuso (Translator) published by Sinolingua, Beijing ISBN 7-80052-507-4 I'm also regularly dipping into "The New Age Concise Chinese - English Dictionary" published by The Commercial Press. Chief Editor, Pan Shaozhong ISBN 7 -100-03448-5/H-878

|

pīnyīn,

pīnyīn,

pīn

means "piece together" and

pīn

means "piece together" and yīn

means "sound", so together we have "piece together sound"

which is another way of saying "pronunciation".

yīn

means "sound", so together we have "piece together sound"

which is another way of saying "pronunciation".  Yes, I know you recognize it as liǎn, meaning

"face", but shush now.

Yes, I know you recognize it as liǎn, meaning

"face", but shush now. yuè.

Next we need to decide how many strokes yuè uses. You might

think that it is five strokes, but you'd be wrong. It's

only four. If you think it is five you could look it up on the

five stroke list, not find it, and then try the four

stroke list where you would have better luck. This is usually

the way it goes for me. Being cleverer than that this time, we

open our dictionary to the radical index page and look at the list

of four stroke radicals.

yuè.

Next we need to decide how many strokes yuè uses. You might

think that it is five strokes, but you'd be wrong. It's

only four. If you think it is five you could look it up on the

five stroke list, not find it, and then try the four

stroke list where you would have better luck. This is usually

the way it goes for me. Being cleverer than that this time, we

open our dictionary to the radical index page and look at the list

of four stroke radicals.  ,

sì at the top of this list means "four" by the way,

the number of strokes used to make the radicals on the list.

We'll get to numbers later. Right now I just want to

get on with this explanation.

,

sì at the top of this list means "four" by the way,

the number of strokes used to make the radicals on the list.

We'll get to numbers later. Right now I just want to

get on with this explanation.  qĭ

is "to stand on tiptoes". And

qĭ

is "to stand on tiptoes". And

é (That's right, just one letter but pronounced with two

syllables like oouh, only quickly) means goose. So

é (That's right, just one letter but pronounced with two

syllables like oouh, only quickly) means goose. So

qĭ é "goose standing on tiptoes", or "penguin". Isn't

that just adorable. A penguin is a goose standing on tiptoes.

I love this language!!!

qĭ é "goose standing on tiptoes", or "penguin". Isn't

that just adorable. A penguin is a goose standing on tiptoes.

I love this language!!!

gǒu shí

gǒu shí

gǒu shì

gǒu shì gǒu

shǐ

gǒu

shǐ  huā

with a flat tone, the first tone, means flower.

With a rising tone, the second tone,

huā

with a flat tone, the first tone, means flower.

With a rising tone, the second tone,

huá

it means slippery. So I

imagine I'm carrying a flower, and about to say the word,

when I slip on some ice and the word comes out with a rising

surprised inflection. Try it. It's fun.

huá

it means slippery. So I

imagine I'm carrying a flower, and about to say the word,

when I slip on some ice and the word comes out with a rising

surprised inflection. Try it. It's fun. huá

huā shēng

jiàng, "smooth peanut butter" .

huá

huā shēng

jiàng, "smooth peanut butter" .  lǎo

shī means "teacher".

lǎo

shī means "teacher".  lǎo

shi (5th tone or no tone) means "honest".

lǎo

shi (5th tone or no tone) means "honest".  lǎo shÍ ( second or

rising tone) is an adverb meaning "always".

lǎo shÍ ( second or

rising tone) is an adverb meaning "always".  lǎo hu (fifth or no tone on hu) means

"tiger".

lǎo hu (fifth or no tone on hu) means

"tiger".  lǎo jiā means

"home town".

lǎo jiā means

"home town".  lǎo dà means

"eldest son".

lǎo dà means

"eldest son".  lǎo rén means

"old person".

lǎo rén means

"old person".  lǎo bǎn means

"shop keeper" or "proprietor".

lǎo bǎn means

"shop keeper" or "proprietor".  lǎo tài tai

means "old lady" (you remember tai, right? Who could

forget? What, you forgot. It made you laugh the first

time you read it.

lǎo tài tai

means "old lady" (you remember tai, right? Who could

forget? What, you forgot. It made you laugh the first

time you read it.

lǎo shŭ means

"mouse"

lǎo shŭ means

"mouse"  Lǎo bǎi xìng.

Literally it means "old hundred names", because most people in

China have one of a mere one hundred family names. So lǎo

bǎi xìng,

"old hundred names" means "common person".

Lǎo bǎi xìng.

Literally it means "old hundred names", because most people in

China have one of a mere one hundred family names. So lǎo

bǎi xìng,

"old hundred names" means "common person".  lǎo po means "old lady" as in "this is my

old lady", or "wife".

lǎo po means "old lady" as in "this is my

old lady", or "wife".  lǎo xiāng means

"fellow villager" or "homey".

lǎo xiāng means

"fellow villager" or "homey".  lao

yī bèi means

"older generation".

lao

yī bèi means

"older generation".  lǎo

yā means "crow" (the bird, not the

verb).

lǎo

yā means "crow" (the bird, not the

verb).  which means an "old folks home" (You recognized ān

there I hope. You got that one in the

which means an "old folks home" (You recognized ān

there I hope. You got that one in the

,literally "hundred old gather together" but here meaning "Broadway"

as in "give my regards to".

,literally "hundred old gather together" but here meaning "Broadway"

as in "give my regards to".  chī jiǎozi lǎo

hu

chī jiǎozi lǎo

hu